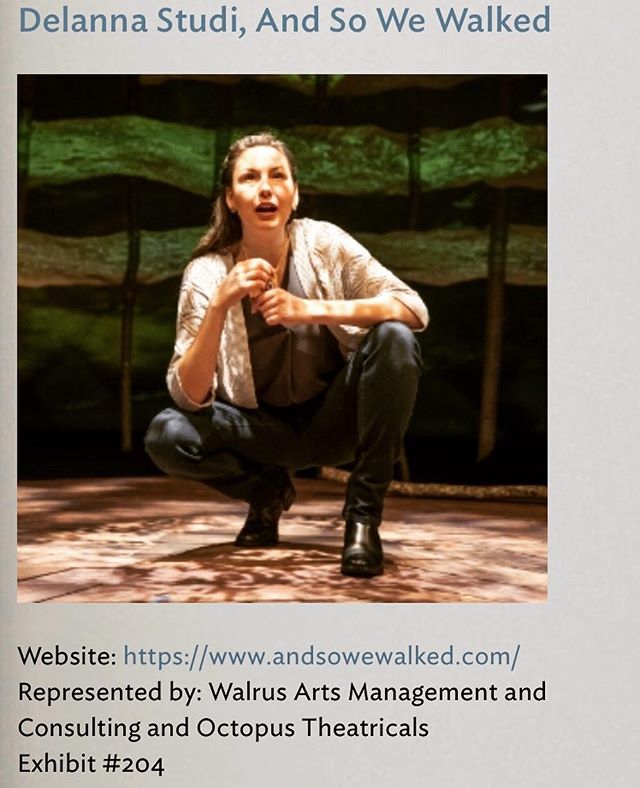

Excerpt from the end of act one

AND SO WE WALKED: An artist's journey

along the trail of tears

Created and Performed by DeLanna Studi (Cherokee Nation)

DELANNA

My dad, Emily and I head out just after dusk for another of my father’s social engagements. Attending the local Stomp Dance. True, I had been hoping my father’s Cherokee-ness would lend me credibility, but I had no idea his popularity would crowd my production calendar. Still, tonight, I am trying to be receptive. As we drive deep into the woods and up a mountain, my dad tells Emily:

DAD

The Ga-ti-yo, Stomp Dance, is a sacred event. Up until 1979, it was illegal for us to practice our religion, our songs, our dances, but we did anyway. We hid out in the hills and we kept the old ways. During the Trail of Tears, the Cherokees who were removed carried the embers of the First Fire to Oklahoma. A very important task because when I say the First Fire, I mean the very First Fire in all of mankind. One hundred and fifty years after the Trail, my Cousin John and some others brought that fire back here from Oklahoma.Tonight, we are going to the late Walker Calhoun’s stomp grounds, one of the Ga-ti-yo where the fire was returned.

EMILY

Wow. He walked all the way back with the fire?

DAD

Walked? He drove it back in his pickup.

DELANNA

And then my father’s laughter rocks our SUV. I see that mischievous glimmer and I know he’s excited.

The directions lead us to a small house, perched on the side of a mountain. We have never formally met any of the dozen or so people gathered, but they are family of the late Walker Calhoun, one of the greatest culture bearers of the Cherokee.

I won’t lie. I’m ready for another Cherokee Inquisition like my meeting with the Cherokee Official; but instead, an elderly woman named Ida says, “Miss Studi! Welcome. We were hoping you would make it.”

We are whisked inside like long-lost family. Dinner is waiting on the table prepared by the women in traditional pot-luck style. The women are seated at one table, the men at another. My father takes his place among the silent men, assuming the stance that I identify only belonging to a Cherokee man: arms folded across the chest, relaxed mouth. Not a frown, but not exactly a smile either. Emily and I are invited to sit with the women who are in the midst of a hushed conversation.

IDA

Annette’s girl? Well… they released her from the hospital and into our rehab facility, but if she doesn’t want to stay there, we can’t make her.

DELANNA

A woman named Twila shakes her head and says...

TWILA

That’s a shame. She’s so young. 17.

IDA

(nodding )

We need another facility to help them all…better programming in schools.

TWILA

Maybe if we had more cultural classes?

IDA

Well, I’ve planted a bug in many a councilman’s ear. Hopefully one will listen.

TWILA

We’ll see. If not, another election is coming up.

DELANNA

I chirp up. Have either of you thought about running for council?

IDA

Run for council? I don’t want to participate in the political mud-slinging. Besides I have more power right here. Planting my bugs. That’s how things get done.

TWILA

The men may be the representatives, but we know who’s really in charge.

DELANNA

We finish our meals and clean the kitchen. “You ladies need help?” a round-bellied man named Bob asks.

IDA

Get out of our kitchen. We’re bonding in here.

DELANNA

I want to bond, to join in with all the women’s laughter, but my mind is elsewhere. Could I ever become a real leader? Do I have that in me? Right now I feel like I am failing to live up to those qualities that make Ida a quiet force to be reckoned with.

TWILA

It’s time. Let’s go to water.

DELANNA

(aside)

I didn’t grow up going to water. In fact, I wasn’t sure what it was until a few years ago. I was visiting John, one of my Cherokee friends in Wisconsin, and we had walked down to the Green Bay

JOHN

Let’s go to water.

DELANNA

Ummm. I don’t think we should get into the water.

JOHN

We won’t be getting in the water. Just kneel down beside it and do this. *

DELANNA

(narrating)

He scoops up a handful of water over his face. Four times.

(to John)

That’s going to water? That’s how we wash our face. Every morning. Ice cold water. Four times.

JOHN

Well, that’s going to water.

DELANNA

My Dad never told me that.

JOHN

He was forced to go to a BIA boarding school, right? He probably had to hide that he was keeping tradition. You can’t get in trouble for washing your face.

DELANNA

Twila’s voice brings me back.

TWILA

You and Emily aren’t on your moons, are you? Your cycle?

EMILY

No, why? Does that make us unclean?

TWILA

(gently laughs)

It makes you more powerful than any medicine. Going to water is like smudging yourself with sage or cedar but with water. Some people do hands, feet, heart, head. Four or seven times. Your choice. But four OR seven. Those are sacred. We cleanse ourselves before we step on the grounds. If you want to say a prayer, well, that’s between you and the Creator.

DELANNA

We crouch next to a mountain stream- water cascades down. The water’s ice cold and as blue as blue could be!

TWILA

This stream comes down from Medicine Lake.

DELANNA

Medicine Lake? I thought that was just a story.

TWILA

There’s no such thing as ‘just a story’ especially in Cherokee. When Yona (Bear) was wounded he made his way to Medicine Lake. He jumped in and swam across. When he crawled out on the other side, his wounds were healed.

DELANNA

(DeLanna washes her face in the water.)

Yona was healed by Medicine Lake? I shudder remembering my dream. Here we are, three women, going to water in one of the most sacred and powerful places in all of Cherokee. Is there healing for me here? Then Twila pulls out two broom-skirts from her bag.

TWILA

Put these on. It’s our version of going to church, Emily.

DELANNA

Night has fallen as Twila leads us silently down a trail towards the stomp grounds. We women walk single file in the shadow of tall trees with only the sound of the stream following us. Though I can’t see the grounds yet, I smell the smoke. Here I am. At the foot of the mountain that is home to Medicine Lake with the smell of the First Fire greeting me! We reach a grassy clearing and I can see foothills and the valley where the town of Cherokee is below, lit by the full moon. I turn and look towards the stomp grounds and see lightening bugs dancing in the trees. I feel all my ancestors beside me and I wonder how I could ever feel lonely again. And I know without looking that my father is right there beside me.

DAD

It’s beautiful. I wish I could bring our whole family here. C’mon. Let’s see if this stomp is different from back home.

DELANNA

We follow the inviting aroma of burning oak. We enter the circular arbor, which sits in a grassy field. Out of the seven clans of the Cherokee, we sit with the clan of our host, the Deer Clan. We are their guests after all. If I were home, I would sit with my father’s clan. Since we’re matrilineal, clans are passed through our mothers and since my mother is white, I am a woman without clan. I don’t belong. I will always be a guest. It’s an intimate gathering of 20 to 30 people. As we sit down on a wooden bench, our neighbor is a handsome young man in a traditional ribbon shirt. He approaches my father.

SAM

I’m Sam. Is this your first time to the stomp grounds?

DAD

(Dad, arms folded, looking just past Sam)

Yes.

SAM

I came for the first time two weeks ago. Have you stomped before?

DAD

Yes.

DELANNA

My dad. What a charmer.

SAM

Do you guys live here in Qualla Boundary?

DAD

No.

DELANNA

Seriously, how does my dad ever make friends?

(to Sam)

We’re from Oklahoma.

SAM

Oh, Oklahoma Cherokee?

DELANNA

My dad grunts this time. Yes.

(to Sam)

We’re Cherokee Nation.

SAM

(focused on Dad)

I’m part Cherokee… not enrolled, but I’m trying to find out my ancestry. I’m doing some research work for school … at Red Clay over in Tennessee… you know the Blue Hole? I’ll gladly give you a private tour, sir. Just let me know.

DAD

Thanks.

(to DeLanna)

Lanna, give him my number.

DELANNA

You probably thought my dad didn’t like Sam. Of course, my dad likes Sam. Sam is just like his children, like me. A young person of Cherokee descent trying to find his place in the world. Trying to walk that thin line between the traditional and the modern. Trying to prove something to ourselves that can’t really be proven. Something that lies in our very bones, our blood memory.

We sit side-by-side listening as the ceremony begins: the fire crackling, the men singing, the women’s turtle shells rattling, the laughter. Fireflies, our own private sentinels, skirt around the sacred circle, never entering. The beat of the water drum guides us and I dance as if I instinctually know all the steps, as if they are etched on my soul. Long forgotten now reawakened.

Even Sam joins in, but my father does not. He says his knee is hurting, but I know he is content taking in the sights and smells. And I realize standing here tonight, with my dad at a stomp grounds that had ties to my family, we both know. We belong.

We are a thousand miles away from Oklahoma, but we are home.